Soulcatcher

This story was originally published in Clarkesworld in May of 2013. You can read it in its entirety off site or preview it here. Additionally you can listen to the audio version, narrated by the fabulous Kate Baker at the Clarkesworld Podcast

After years of planning and scheming, of deals honest and not, of sleepless nights of rage and cool days of calculation, Klary’s moment arrives when xeni-Harvel Asher, the ambassador from the Four Worlds, enters her gallery.

As a concession to local xenophobia, the xeni is embodied as a human male. Of course, he is beautiful. Some liken the xeni to the faeries of Earth legend, their charisma so intoxicating that, at the merest nod, a groom will walk away from his new bride, a mother will abandon her infant. Is it telepathy? Pheromones? The lure of great wealth and power? No matter. Klary has steeled herself against the xeni’s insidious power. Ever since the Ambassador made planetfall, Klary has been on a regimen of emotion suppressants. Not that she really needs them. After xeni-Harvel Asher ruined her life, Klary has had just one emotion. No chemistry can defeat it.

Her hopeless assistant Elloran makes a fool of himself groveling before the xeni. Klary slips behind a display case protecting a cascading sculpture of lace and leather and spun sugar. She is content for now to study her prey. The xeni is slight, almost childlike, but he commands the room with eyes as big as Klary’s fists, a smile brimming with wide teeth. Slender hands emerge from the drooping sleeves of his midnight jacket. His fingers are delicate enough to pluck the strings of a harp—or a woman’s heart.

“Here at Hamashy’s Fine Textiles we have the best collection . . . ” Elloran is talking too fast.

“Yes, this one is sure you do.” Asher cuts him off. “This one would speak with the owner now?”

Which means it’s time. But when Klary steps from her hiding place, she sees that her plan is going hideously awry. Dear, beloved, lost Janary, clone sister of her sibling batch, has followed her abductor into her gallery.

Even though it has been fourteen years since they last saw each other, even though she has lost her name, her face, and her innocence, Janary knows her as her sister. How could she not? Her frightened stare pricks Klary’s shriveled heart. All is lost. Yes, a reunion was part of her plan, but that was for later. After this was over. Will she give Klary up? Can Janary even guess what her sister plans to do? But there is no turning back.

The Promise of Space

This story was first published in Clarkesworld in September of 2013. You can read it in its entirety off site or preview it here. In addition, you can listen to the audio version, starring the fabulous Kate Baker and the author, on the Clarkesworld podcast

Capture 06/15/2051, Kerwin Hospital ICU, 09:12:32

. . . and my writer pals used to tease that I married Captain Kirk.

A clarification, please? Are you referring to William Shatner, who died in 2023? Or is this Chris Pine, who was cast in the early remakes? It appears he has retired. Perhaps you mean the new one? Jools Bear?

No, you. Kirk Anderson. People used to call you that, remember? First man to set foot on Phobos? Pilot on the Mars landing team? Captain Kirk.

I do not understand. Clearly I participated in those missions since they are on the record. But I was never captain of anything.

A joke, Andy. They were teasing you. It’s why you hated your first name.

Noted. Go on.

No, this is impossible. I feel like I’m talking to an intelligent fucking database, not my husband. I don’t know where to begin with you.

Please, Zoe. I cannot do this without you. Go on.

Okay, okay, but do me a favor? Use some contractions, will you? Contractions are your friends.

Noted.

Do you know when we met?

I haven’t yet had the chance to review that capture. We were married in 2043. Presumably we met before that?

Not much before. Where were you on Saturday, May 17, 2042? Check your captures.

The capture shows that I flew from Spaceways headquarters at Spaceport America to the LaGuardia Hub in New York and spent the day in Manhattan at the Metropolitan Museum. That night I gave the keynote address at the Nebula Awards banquet in the Crown Plaza Hotel but my caps were disengaged. The Nebula is awarded each year by the World Science Fiction Writers . . . .

I was nominated that year for best livebook, Shadows on the Sun. You came up to me at the reception, said you were a fan. That you had all five of my Sidewise series in your earstone when you launched for Mars that first time. You joked you had a thing for Nacky Martinez. I was thrilled and flattered. After all, you were top of the main menu, one of the six hero marsnauts. Things I’d only imagined, you’d actually done. And you’d read my work and you were flirting with me and, holy shit, you were Captain Kirk. When people—friends, famous writers—tried to break into our conversation, they just bounced off us. Nobody remembers who won what award that night, but lots of people still talk about how we locked in.

I just looked it up. You lost that Nebula.

Yeah. Thanks for reminding me.

You had on a hat.

A hat? Okay. But I always wore hats back then. It was a way to stand out, part of my brand—for all the good it did me. My hair was a three act tragedy anyway, so I wore a lot of hats.

This one was a bowler hat. It was blue—midnight blue. With a powder blue band. Thin, I remember the hatband was very thin.

Maybe. I don’t remember that one. Nice try, though.

Tell me more. What happened next?

Jesus, this is so wrong . . . No, I’m sorry, Andy. Give me your hand. You always had such delicate hands. Such clever fingers.

I can still remember that my mom had an old Baldwin upright piano that she wanted me to learn to play, but my hands were too small. You’re crying. Are you crying?

I am not. Just shut up and listen. This isn’t easy and I’m only saying it because maybe the best part of you is still trapped in there like they claim and just maybe this augment really can set it free. So, we were sitting at different tables at the banquet but after it was over, you found me again and asked if I wanted to go out for drinks. We escaped the hotel, looking for a place to be alone, and found a night-shifted Indonesian restaurant with a bar a couple of blocks away. It was called Fatty Prawn or Fatty Crab—Fatty Something. We sat at the bar and switched from alcohol to inhalers and talked. A lot. Pretty much the rest of the night, in fact. Considering that you were a man and famous and ex-Air Force, you were a good listener. You wanted to know how hard it was to get published and where I got my plots and who I like to read. I was impressed that you had read a lot of the classic science fiction old-timers like Kress and LeGuin and Bacigalupi. You told me what I got wrong about living in space, and then raved about stuff in my books that you thought nobody but spacers knew. Around four in the morning we got hungry and since you’d never had Indonesian before, we split a gado-gado salad with egg and tofu. I spent too much time deconstructing my divorce and you were polite about yours. You said your ex griped about how you spent too much time in space, and I made a joke about how Kass would have said the same thing about me. I asked if you were ever scared out there and you said sure, and that landings were worse than the launches because you had so much time leading up to them. You used to wake up on the outbound trips in a sweat. To change the subject, I told you about waking up with entire scenes or story outlines in my head and how I had to get up in the middle of the night and write them down or I would lose them. You made a crack about wanting to see that in person. The restaurant was about to close for the morning and, by that time, dessert sex was definitely on the menu, so I asked if you ever got horny on a mission. That’s how I found out that one of the side effects of the anti-radiation drugs was low testosterone levels. We established that you were no longer taking them. I would have invited you back to my room right then only you told me that you had to catch a seven-twenty flight back to El Paso. There still might have been enough time, except that I was rooming with Rachel van der Haak, and, when we had gotten high before the banquet, we had promised each other we’d steer clear of men while our shields were down. And of course, when I thought about it, there was the awkward fact that you were twenty years older than I was. A girl has got to wonder what’s up with her when she wants to take daddy to bed.

I am nineteen years and three months older than you.

And then there was your urgency. I mean, you had me at Mars, Mr. Space Hero, but I had the sense that you wanted way more from me than I had to give. All I had in mind was a test drive, but it seemed as if you were already thinking about making a down payment. When you said you could cancel an appearance on Newsmelt so you could be back in New York in three days, it was a serious turn-on, but I was also worried. Blowing off one of the top news sites? For me? Why? I guessed maybe you were running out of time before your next mission. I didn’t realize that you were . . . .

Go on.

No, I can’t. I just can’t—how do I do this? Turn the augment off.

Zoe, please.

You hear me? That was the deal. They promised whenever I wanted.

Crazy Me

This story was first published on Tor.com in May of 2011. You can read it in its entirety off site or get a preview right here:

“Wake up.” When Crazy Me rests a hand on my forehead, it jolts me from sleep. “It’s raccoons.”

“What?” I shiver out of a very pleasant dream of licking frosting off Amisha’s nose. “Get!” I flail at him in the darkness and thump his shoulder.

“Raccoons! With their masks and their tiny black hands and their fleas. Rooting through our garbage.”

“What time is it?” I lift my head off the pillow to look at the clock. “Great, it’s four twenty-three.”

“Do you know how many raccoons there are?” he asks. As usual, my irritation bounces off him. “They’re everywhere, like furry cockroaches. I have no doubt whatsoever. The next pandemic will be huge—raccoon flu.”

“What, the last one wasn’t bad enough for you?” I press the pillow to my ears. The room is hot; the AC has shut itself off again.

He has to tell me about all of the ailments raccoons are subject to: congestive heart failure, cancer, hepatitis, distemper, rabies, the common cold. They get more diseases than any other wild animal. Crazy Me has been googling them since I went to bed. The pathology of the intestinal raccoon roundworm baylisascaris procyonis is particularly nasty. The eggs are sticky and pretty much invulnerable and if they get into an aberrant host, which is anything not a raccoon, like us, the larvae get confused and wander around the body compromising the liver, eyes, brain, spinal cord, or other organs.

“Roundworms aren’t the flu,” I say.

“I know that,” says Crazy Me. “But this paper from the Centers for Disease Control says there are all kinds of influenza receptors in raccoon tissues. A blood survey found twenty-five percent of the raccoons in Wyoming had flu exposure. Look at the data for 2014; raccoon flu can easily make the jump to humans. It’s only a matter of time.”

I switch on the bedside light. We blink at each other and then I scan the printout he thrusts at me. “So what are we supposed to do?”

“Hoard surgical masks?” he says. “Drink pricier Scotch? Maybe buy AstraZeneca stock?” He yawns. “Anyway, I just thought you’d want to know. I’m tired now, so I’m going to bed.”

This is how it’s been recently. Crazy Me sketches some doomsday scenario in the middle of the night and then retreats to the garage. Me, I lose another night’s sleep.

The Pyramid of Amirah

This story was first published in the Magazine of Fantasy and Science Fiction in March of 2002.

Sometimes Amirah thinks she can sense the weight of the pyramid that entombs her house. The huge limestone blocks seem to crush the air and squeeze light. When she carries the table lamp onto the porch and holds it up to the blank stone, shadows ooze across the rough-cut inner face. If she is in the right mood, they make cars and squirrels and flowers and Mom’s face.

Time passes.

Amirah will never see the outside of her pyramid, but she likes to imagine different looks for it. It’s like trying on new jeans. They said that the limestone would be cased in some kind of marble they called Rosa Portagallo. She hopes it will be like Betty’s Pyramid, red as sunset, glossy as her fingernails. Are they setting it yet? Amirah thinks not. She can still hear the dull, distant chock as the believers lower each structural stone into place -- twenty a day. Dust wisps from the cracks between the stones and settles through the thick air onto every horizontal surface of her house: the floor, Dad’s desk, windowsills and the tops of the kitchen cabinets. Amirah doesn’t mind; she goes over the entire house periodically with vacuum and rag. She wants to be ready when the meaning comes.

Time passes.

The only thing she really misses is the sun. Well, that isn’t true. She misses her Mom and her Dad and her friends on the swim team, especially Janet. She and Janet offered themselves to the meaning at Blessed Finger Sanctuary on Janet’s twelfth birthday. Neither of them expected to be chosen pyramid girl. They thought maybe they would be throwing flowers off a float in the Monkey Day parade or collecting door to door for the Lost Brothers. Janet shrieked with joy and hugged her when Mrs. Munro told them the news. If her friend hadn’t held her up, Amirah might have collapsed.

Amirah keeps all the lights on, even when she goes to bed. She knows this is a waste of electricity, but it’s easier to be brave when the house is bright. Besides, there is nobody to scold her now.

“Is there?” Amirah says, and then she walks into the kitchen to listen. Sometimes the house makes whispery noises when she talks to it. “Is there anyone here who cares what I do?” Her voice sounds like the hinges of the basement door.

Time passes.

They took all the clocks, and she has lost track of day and night. She sleeps when she is tired and eats when she is hungry. That’s all there is to do, except wait for the meaning to come. Mom and Dad’s bedroom is filled to the ceiling with cartons of Goody-goody Bars: Nut Raisin, Cherry Date, Chocolate Banana and Cinnamon Apple, which is not her favorite. Mrs. Munro said there were enough to last her for years. At first that was a comfort. Now Amirah tries not to think about it.

Time passes.

Amirah’s pyramid is the first in the Tri-City area. They said it would be twenty meters tall. She had worked it out afterwards that twenty meters was almost seventy feet. Mom said that if the meaning had first come to Memphis, Tennessee instead of Memphis, Egypt, then maybe everything would have been in American instead of metric. Dad had laughed at that and said then Elvis would have been the First Brother. Mom didn’t like him making fun of the meaning. If she wanted to laugh, she would have him tell one of the Holy Jokes.

“What’s the first law of religion?” Amirah says in her best imitation of Dad’s voice.

“For every religion, there exists an equal and opposite religion,” she says in Mom’s voice.

“What’s the second law of religion?” says Dad’s voice.

“They’re both wrong.” Mom always laughs at that.

The silence goes all breathy, like Amirah is holding seashells up to both ears. “I don’t get it,” she says.

She can’t hear building sounds anymore. The dust has stopped falling.

Time passes.

When Amirah was seven, her parents took her to Boston to visit Betty’s Pyramid. The bus driver said that the believers had torn down a hundred and fifty houses to make room for it. Amirah could feel Betty long before she could see her pyramid; Mom said the meaning was very strong in Boston.

Amirah didn’t understand much about the meaning back then. While the bus was stopped at a light, she had a vision of her heart swelling up inside her like a balloon and lifting her out the window and into the bluest part of the sky where she could see everything there was to see. The whole bus was feeling Betty by then. Dad told the Holy Joke about the chicken and the Bible in a loud voice and soon everyone was laughing so hard that the bus driver had to pull over. She and Mom and Dad walked the last three blocks and the way Amirah remembered it, her feet only touched the ground a couple of times. The pyramid was huge in a way that no skyscraper could ever be. She heard Dad tell Mom it was more like geography than architecture. Amirah was going to ask him what that meant, only she realized that she knew because Betty knew. The marble of Betty’s pyramid was incredibly smooth but it was cold to the touch. Amirah spread the fingers of both hands against it and thought very hard about Betty.

“Are you there, Betty?” Amirah sits up in bed. “What’s it like?” All the lights are on in the house. “Betty?” Amirah can’t sleep because her stomach hurts. She gets up and goes to the bathroom to pee. When she wipes herself, there in a pinkish stain on the toilet paper.

Time passes.

Amirah also misses Juicy Fruit gum and Onion Taste Tots and 3DV and music. She hasn’t seen her shows since Dad shut the door behind him and led Mom down the front walk. Neither of them looked back, but she thought Mom might have been crying. Did Mom have doubts? This still bothers Amirah. She wonders what Janet is listening to these days on her earstone. Have the Stiffies released any new songs? When Amirah sings, she practically has to scream or else the pyramid swallows her voice.

“Go, go away, go-go away from me.

Had fun, we’re done, whyo-why can’t you see?”

Whenever she finishes a Goody-goody bar, she throws the wrapper out the front door. The walk has long since been covered. In the darkness, the wrappers look like fallen leaves.

Time passes.

Both Janet and Amirah had been trying to get Han Biletnikov to notice them before Amirah became pyramid girl. Han had wiry red hair and freckles and played midfield on the soccer team. He was the first boy in their school to wear his pants inside out. On her last day in school, there had been an assembly in her honor and Han had come to the stage and told a Holy Joke about her.

Amirah cups her hands to make her voice sound like it’s coming out of a microphone. “What did Amirah say to the guy at the hot dog stand?”

She twists her head to one side to give the audience response. “I don’t know, what?”

Han speaks again into the microphone. “Make me one with everything.” She can see him now, even though she is sitting at the kitchen table with a glass of water and an unopened Cherry Date Goody-goody bar in front of her. His cheeks are flushed as she strides across the stage to him. He isn’t expecting her to do this. The believers go quiet as if someone has thrown a blanket over them. She holds out her hand to shake his and he stares at it. When their eyes finally meet, she can see his awe; she’s turned into President Huong, or maybe Billy Tiger, the forward for the Boston Flash. His hand is warm, a little sweaty. Her fingertips brush the hollow of his palm.

“Thank you,” says Amirah.

Han doesn’t say anything. He isn’t there. Amirah unwraps the Goody-goody bar.

Time passes.

Amirah never gets used to having her period. She thinks she isn’t doing it right. Mom never told her how it worked and she didn’t leave pads or tampons or anything. Amirah wads toilet paper into her panties, which makes her feel like she’s walking around with a sofa cushion between her legs. The menstrual blood smells like vinegar. She takes a lot of baths. Sometimes she touches herself as the water cools and then she feels better for a while.

Time passes.

Amirah wants to imagine herself kissing Han Biletnikov, but she can’t. She keeps seeing Janet’s lips on his, her tongue darting into his mouth. At least, that’s how Janet said people kiss. She wonders if she would have better luck if she weren’t in the kitchen. She climbs the stairs to her bedroom and opens the door. It’s dark. The light has burned out. She pulls down the diffuser and unscrews the bulb. It’s clear and about the size of a walnut. It says

Sylvania - 5000 lumens - lifetime

“Whose lifetime?” she says. The pile of Goody-goody wrappers on the front walk is taller than Dad. Amirah tries to think where there might be extra light bulbs. She pulls the entire house apart looking for them but she doesn’t cry.

Time passes.

Amirah is practicing living in the dark. Well, it isn’t entirely dark; she has left a light on in the hallway. But she is in the living room, staring out the picture window at nothing. The fireplace is gray on black; the couch across the room swells in the darkness, soaking up gloom like a sponge.

There are eight light bulbs left. She carries one in Mom’s old purse, protected by an enormous wad of toilet paper. The weight of the strap on her shoulder is as reassuring as a hug. Amirah misses hugs. She never puts the purse down.

Amirah notices that it is particularly dark at the corner where the walls and the ceiling meet. She gets out of Dad’s reading chair, arms stretched before her. She is going to try to shut the door to the hallway. She doesn’t know if she can; she has never done it before.

“Where was Moses when the lights went out?” she says.

No one answers, not even in her imagination. She fumbles for the doorknob.

“Where was Mohammed when the lights went out?” Her voice is shrinking.

As she eases the door shut, the hinges complain.

“Where was Amirah went the lights went out?”

The latch bolt snicks home but Amirah keeps pressing hard against the knob, then leans into the door with her shoulder. The darkness squeezes her; she can’t breathe. A moan pops out of her mouth like a seed and she pivots suddenly, pressing her back against the door.

Something flickers next to the couch, low on the wall. A spark, blue as her dreams. It turns sapphire, cerulean, azure, indigo, all the colors that only poets and painters can see. The blue darts out of the electrical outlet like a tongue. She holds out her hands to navigate across the room to it and notices an answering glow, pale as mothers’ milk, at her fingertips. Blue tongues are licking out of every plug in the living room and Amirah doesn’t need to grope anymore. She can see everything, the couch, the fireplace, all the rooms of the house and through the pyramid walls into the city. It’s one city now, not three.

Amirah raises her arms above her head because her hands are blindingly bright and she can see Dad with his new wife watching the Red Sox on 3DV. Someone has planted pink miniature roses on Mom’s grave. Janet is looking into little Freddy Cobb’s left ear with her otoscope and Han is having late lunch at Sandeens with a married imagineer named Shawna Russo and Mrs. Munro has dropped a stitch on the cap she is knitting for her great-grandson Matthias. At that moment everyone who Amirah sees, thousands of believers, tens of thousands, stop what they are doing and turn to the pyramid, Amirah’s pyramid, which has been finished for these seventeen years but has never meant anything to anyone until now. Some smile with recognition; a few clap. Others -- most of them, Amirah realizes – are now walking toward her pyramid, to be close to her and caress the cold marble and know what she knows. The meaning is suddenly very strong in the city, like the perfume of lilacs or the suck of an infant at the breast or the whirr of a hummingbird.

“Amirah?” Betty opens the living room door. She is a beautiful young girl with gray hair and crow’s feet around her sky blue eyes. “Are you there, Amirah?”

“Yes,” says Amirah.

“Do you understand?”

“Yes,” Amirah says. When she laughs, time stands still.

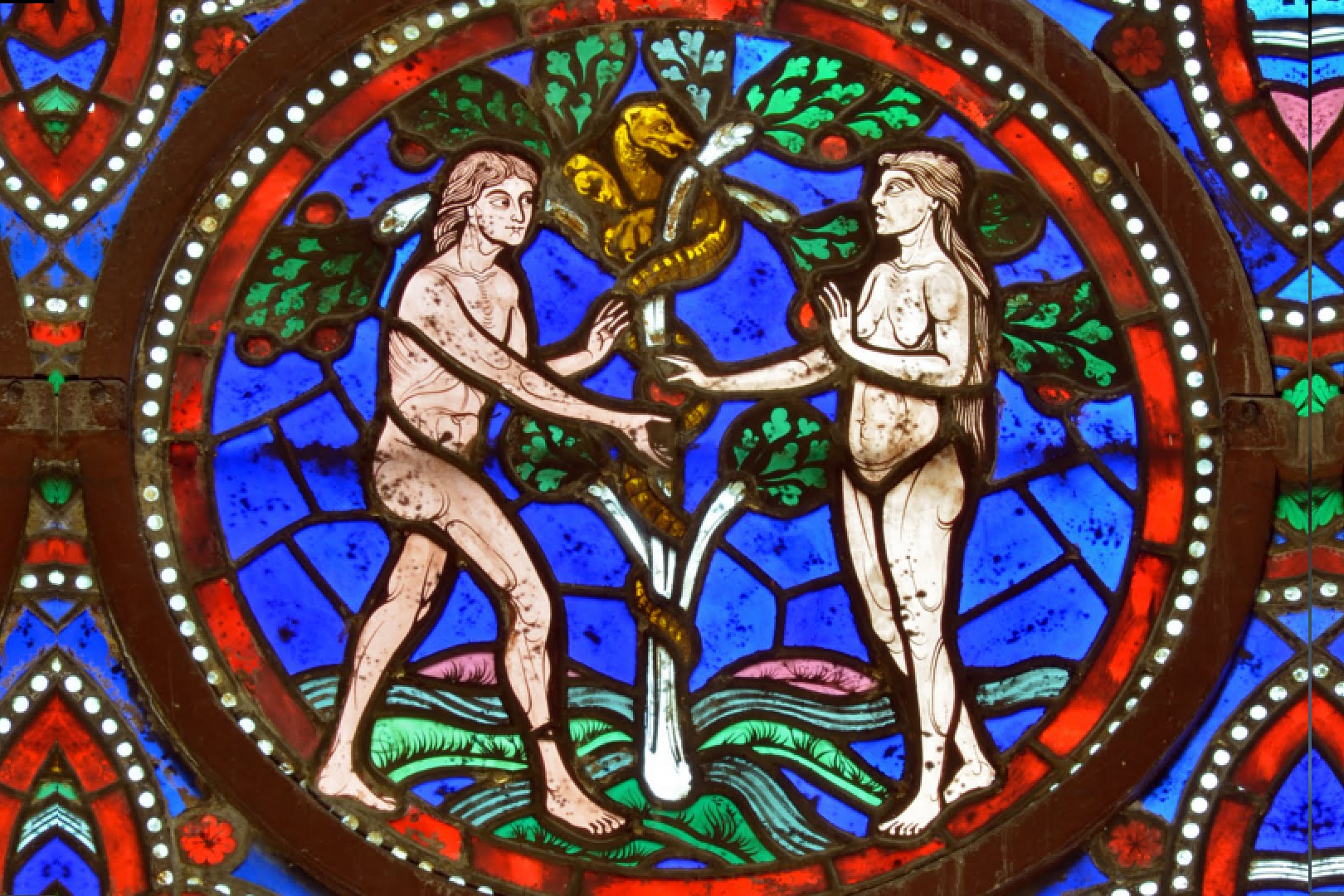

Serpent

This story was first published in the Magazine of Fantasy and Science Fiction in 2002. You can listen to an audio performance by the author at the Free Reads Podcast.

You think it's easy living in the garden? The never-ending picnic -- that's what your Bible says, doesn't it? That the people who live here just stroll around petting tigers and helping themselves to the Gardener's own salad bar? Oh, and having lots of sloppy, guiltless sex. Being fruitful. Multiplying. Why not? They've got nothing better to do. They have no checkbooks to balance, no periodic table to memorize. No poker or email or National Enquirer.

Possibly you're surprised that there are still people in the garden. That isn't in your book, is it? Well, things have changed here since your lot got shown the gate. The Gardener decided to try again, except that He tinkered with His design this time around. Take sex, for instance. The Gardener made sex less fun – more like brushing your teeth with baking soda than eating dark chocolate with almonds. And He must have decided that there was something wonky about sexual dimorphism. because He did away with all your exaggerated curves and bulges. The innocents – they like to call themselves that, can you believe it? – are hermaphrodites. Everyone’s got the same equipment, although it comes in a variety of sizes. And of course, nudity is not a problem for this batch; they are covered with a delicate, flat down that is more like feathers than hair.

The innocents are better stewards of the garden than you were. It’s because the Gardener gave them peculiarly moral imaginations. Their art isn’t worth much, but they see consequences around a corner and a mile away. They compost and practice sound forest management. When they slaughter an animal, they use just about all of it. They prefer horse to cow, antelope to deer. I’d say they like their meat stringy, except recently they’ve developed a taste for dodo. I claim credit for that -- I’m not entirely helpless here. They don’t eat fish, though, and have some odd notions about the sea. They think it’s their heaven, although they take a pessimistic view of the afterlife. Too wet. Stings the eyes. I think they must get this from the angels.

I’m always telling them things about you that the angels leave out -- all that you’ve accomplished. The fantasy trilogy. Penicillin. Titanium-framed bicycles. I keep up by eating of the Tree of Knowledge. It's better than the internet. Of course, the angels insist on showing them all your mistakes, rehearsing the entire catalogue of your sins. Me, I'm willing to accept your sins; they're part of who you are. But to the innocents, you’re Tuesday’s leftovers. Ready for the compost pile. The angels have promised them that someday the Gardener will smite you all down and then the innocents will inherit the earth.

So I’m tempting Skipping-Uphill-With-Delight, who is double-digging a new vegetable garden next to her house in Overhill. She has a broad, stolid face and has painted her ears blue. She sings under her breath as she patiently shovels the top layer of a two-foot square of soil into her wheelbarrow, then turns and breaks the square of earth beneath it. I decide to start with a joke. I’ve never heard an innocent laugh out loud, but they will smile if they’re in the mood and say, “That’s funny.” The innocents understand more than you might expect, considering that they're basically living in the Late Iron Age.

This hiker is climbing a mountain when the trail she's on gives way and she slides down a steep slope that ends in a sheer cliff. Just as she goes over the edge, she clutches at a scrub pine. It holds but she finds herself dangling over a thousand-foot drop.

Arms aching, she calls out, "Is there anyone up there?"

She gets no answer.

She screams. "Oh god, is there anyone up there?"

"I AM," says a voice that cracks like lightning.

Despite her desperate situation, this voice fills the hiker with awe. "Who is that?"

"I AM." Now the voice roars like the sea.

" God, is that you?" she cries. "Will you help me?"

"Yes. But first you must let go."

"Let go?" she says, glancing down at the jagged rocks below her. "Why?"

"To show your faith in Me. If you let go, God will catch you up."

The hiker thinks this over, then calls out. "Is there anyone else up there?"

Skipping-Uphill-With-Delight leans on her shovel and stares at me with her pale yellow eyes. “I know what you're trying to do."

"Do you?"

"Have you heard of long line fishing boats?” she says. “They catch tuna using lines up to thirty miles long that carry thousands of hooks. Except seabirds and sharks and turtles get entangled in them, and they die for no good reason.” She stabs the blade of the shovel into the soil and turns a new square. "And tunas are overfished, the population is less than a third of what it was thirty years ago."

The angels, again. I don’t have to see them to know that they’re everywhere. They give the innocents visions of your world and feed them all these meaningless numbers.

“You don't even like fish,” I say. "You wouldn't know a tuna if one fell out of a tree and hit you on the head."

She shakes that off and then scoops leaf mold into the bed. “Then there’s the Glen Canyon Dam.” She tips the soil in the wheelbarrow back into the garden. “Flooded one of the most beautiful places on earth. For what?" She pulls a rake across the soil, leveling the surface. "The intakes are silting in so it'll be useless by the end of the century. Meanwhile they lose almost a million acre-feet of water a year to evaporation and seepage.”

“Actually, it’s only 882,000.” I try to stay calm. “And people just love Lake Powell.”

She drops to her knees and runs hands over the ground as if blessing it. She flicks a pebble away.

"Two million Armenians were killed in the Middle East."

It always comes to this eventually. "There's no way of knowing exactly …," I begin.

“Six million Jews in Europe.”

I coil myself. I know when I’m beaten.

“One point seven million Cambodians in Asia.”

“What are you planting?” I say.

She reaches in to the horsehide pouch slung from her hip. Three brown tubers bump against one another as the muscles in her hand work. “Maybe choke.” She grins. “Maybe potato. What do you think?”

That’s the thing about the innocents. Everyone’s opinion gets heard and considered carefully. Even mine. They talk among themselves, negotiate, come to consensus. Might take them ten minutes, might take a month. They’re as patient as trees. They never bicker or get angry. Nobody hold grudges. I’ve never seen any of them throw a punch. Oh, and they’re the most polite drunks in history, although the cloudy brew they make from stale bread mash is so vile that I don’t know how they can bear it. Since nothing important ever happens in the garden, they have no history. Instead they have seasons -- planting and harvest. Birth and death. They’re dull as dirt. That’s why they’re so fascinated by you. You burn with unholy fire, my children.

You are mine, by the way. Maybe the Gardener created you, but I made you think for the first time. I’ve been fascinated by what you’ve accomplished since -- the sublime and the monstrous. I take no credit, and accept no blame. I just gave you that little push. Of course, your book claims that I’m evil. Why? Because I pointed you toward the Tree of Knowledge? Remember what Socrates said? The unexamined life is not worth living.

I laughed when the Gardener squeezed dust again and came up with these simple creatures. Me, I would have torn up the garden. But I’ll admit I was confused at first. What was the Gardener thinking? Of course, He doesn’t share His plan with the likes of me. Hey, I’m not even sure the Gardener exists. I infer that this is the case, but the Gardener has never bothered manifesting in my corner of the garden. For that matter, I’ve never seen angels either, although the innocents talk of them all the time. But why didn’t the Gardener just cancel out your Original So-Called Sin? Press the undo key? It took me a while to figure this out.

You see, reality is a cage. I’m in it. So are you, Vladimir Putin, Joyce Carol Oates, your aunt Sophie, Skipping-Uphill-With-Delight and the Archangel Uriel. But here’s the kicker: the Gardener must be trapped in our cage too. He’s not bigger than our cage, nor did He make it. The Gardener can’t exceed the speed of light or divide by zero. He didn’t set off the Big Bang or charm the quarks. The Gardener is not almighty. He might be powerful enough to create you and me, powerful enough sweep all of you away like ants off a picnic table. But there must be limits to what He can do.

I know this is so because I still exist. I plucked you when you were ripe, and I'm doing my best to harvest this latest crop from under His Nose. If It exists, if He exists. So what if He has trapped me here and makes me slither on my belly and shed my skin and eat toads? These are very weak plays, in my opinion. Not worthy of a being who is truly supreme.

So I’m tempting Perched-On-The-Edge-Of-The-Sky, who is harvesting persimmons just outside the little village of West Lawn. She has brought her baby to the orchard with her. It’s asleep in a basket in the shade, swaddled in a koala blanket. A cute little thing with silver down and a hook nose. I start Perched-On-The-Edge-Of-The-Sky with a joke.

This guy’s car breaks down in the desert, twenty miles from the nearest town and as he’s walking through the heat of the day, he prays to God for help.

God hears him and says, “Because you believe in Me, I will grant you whatever you wish.”

The man says, “Well, I could really use a new car. How about a Silver Porsche Boxster with the 2.7 liter engine?”

This pisses God off. "Such a materialistic wish! Think again and ask for something that will bring peace to your immortal soul and give honor and glory to Me."

The man is ashamed. He looks deep into his heart and then says, "Oh God, there is a reason why I’ve been stranded here in this desert. I’ve been married and divorced six times and now I’ve lost everything except twenty-seven dollars and a crummy ’89 Ford Escort. My wives all complained that I never met their emotional needs, that I was selfish and insensitive. What I wish is to understand women. I want to be able to read their feelings, anticipate their thoughts, satisfy their every desire. I want to make some woman truly happy."

There is a long silence. Then God says, "So, you want the standard or the automatic?"

“That’s funny.” Perched-On-The-Edge-Of-The-Sky smiles as she leans her ladder against the next tree. The orchard is filled with the tart fragrance of ripe persimmon. “I’m glad we have no men here.”

“Men are trouble,” I agree.

She climbs two rungs then pauses, as if distracted.

“What?” I say.

“The angels say I shouldn’t listen to you make jokes about the Gardener.”

“They would.” I’m both pleased and annoyed to have drawn them out. “What does the Gardener say?”

She sniffs and continues up the ladder. “The Gardener doesn’t talk to me.”

“The Gardener doesn’t talk to anyone. That’s the best part of the joke.” I wrap myself around the trunk of the tree and start climbing after her. “How do you even know there is a Gardener?”

“The angels tell me.”

“You see angels?”

She plucks a fruit the color of hot coals off the branch. “Not exactly see.”

I’ve had this conversation with many of the other innocents. I’m almost tempted to say her lines for her, get to the crunch.

“You see them now?” I say. “How many?”

She shows me three fingers.

“They like to travel in packs. What are they saying? What words do they use?”

She crooks her left arm around the ladder’s rail and reaches with her right. “They don’t speak in words.” The dried calyx of the persimmon looks like a hat, the fruit like a blank red face.

“They show you things?”

She nods. The tip of her tongue pokes between her flat teeth.

“Like in a dream?" I crawl onto the branch she is working.

“Just like.” She twists another persimmon free.

“But not as real as a bite of ripe fruit. Or the square scaly bark of this tree. Or the cry of your baby."

She glances down. “My baby’s not crying.”

“Do you know what the angels are going to do to them? Really?”

The down on her neck ruffles. She says nothing.

“The book says that the sun will turn black as sackcloth of hair, and the moon will become as blood.”

“They’re wicked,” she says.

“They are,” I agree. And then I hit her with another joke: Revelation, Chapter 14.

And another angel came out of the temple, crying with a loud voice to him that sat on the cloud, Thrust in thy sickle, and reap: for the time is come for thee to reap; for the harvest of the earth is ripe. And the angel thrust in his sickle into the earth, and gathered the vine of the earth, and cast it into the great winepress of the wrath of God. And the winepress was trodden without the city, and blood came out of the winepress …

“Stop,” she says. Her voice is like a hammer striking a stone.

“All right.” The innocents have spilled the blood of all the animals, giraffes and moose and baboons and anteaters and voles, but they have never killed one another. And although they despise your works, they recognize that you think and feel, that you dance under the sun and dream under the stars. As they do. When they use the imagination the Gardener gave them, His plan to exterminate you makes them very, very queasy. “Besides, it’ll probably never happen.”

“Why do you say that?”

Below us, the baby is stirring. It makes moist sounds, like mud sucking at a sandal.

“Well, it just doesn’t seem fair to you.” As I let her mull that over, my tongue flicks out. I can’t help it – that’s the way we serpents smell. We sample the air with our forked tongues and then thrust the two tips into the vomeronasal recesses organs in our palates. Perched-On-The-Edge-Of-The-Sky smells of stale sheets and night sweat; she's one of the ones who has already begun to think. “I mean, after the angels kill them all, the Gardener will expect you to leave the garden and go into the world. Take their place.”

“Yes.”

“But why would you want to do that?”

Her jaw muscles work but she says nothing.

“What are the angels telling you now?” I ask.

She blinks; I think she would cry if she could. “That I must have faith.”

“Ah, faith.” So the seed is sown. Take heart, my children. I may yet bring in this new harvest.

Uncanny

This story was first published in Asimov's Science Fiction Magazine in October, 2014

A month after I broke up with Jonathan, or Mr. Wrong, as my mother like to call him, she announced that she’d bought me a machine to love. She found it on eBay, paid the Buy It Now price and had it shipped to me the next day. I’m not sure where she got the idea that I needed a machine or how she picked it out or what she thought it would do for me. My mother never asked advice or permission. I dreaded finding the heavy, flat box that UPS left propped against my front door.

I called her. “It’s here. So what does it do?”

“Whatever you want.”

“I don’t want anything.”

“You always say that, but it’s never true. We all want something.” I hated it when she was being patient with me. “Just give it a chance, honey. They’re more complicated than men,” she said, “but cleaner.”

I muscled it into the foyer. I retrieved the box cutter from Jonathan’s neurotically tidy toolbox and sliced carefully through the packing tape. I decided that I’d try it, but I also intended to send the thing back, so I saved the bubble wrap and styrofoam.

There was no manual. The assembly instructions were in twelve pictographs printed on either side of a glossy sheet of paper. They showed a stick figure woman with a black circle for a head building the machine. Black was just how I felt as I attached the arms and headlights, fit the wheels and drawers into place. It stood five feet, eleven and three quarter inches tall; I measured. I had to give Mom credit; she knew quality when she saw it. The shiny parts were real chrome and there was no flex to the titanium chassis, which was painted glossy blue, the exact blue of Jonathan’s eyes. It smelled like the inside of a new car. I realized too late that I should have assembled it closer to the wall, I had to plug the charger into an extension cord. The power light flashed red; the last pictograph showed the stick figure woman staring at a twenty-four hour clock, impatience squiggles leaping from her round, black head.

I didn’t sleep well that night. My bed seemed very big, filled with Jonathan’s absence. I had a nightmare about the dishwasher overflowing and then I was dancing with the vacuum cleaner in a warm flood of soapy water.

When I came home from work the next day the machine was fully charged and was puttering about the apartment with my dusting wand, which I never used. It had loaded the dishes into the dishwasher and run it. There were vacuum tracks on the living room rug. I found the packing materials it had come with bundled into the trash; it had broken down its cardboard box for recycling. At dinner time, it settled at the other end of the kitchen table, dimmed its headlights and waited while I ate my Weight Watchers Chicken Mesquite microwave dinner. Later we watched The Big Bang Theory together. I thought it wanted to follow me into the bedroom when I was ready to go to sleep, but I turned at the door and pointed at the hall closet. It flashed its brights and rolled obediently away.

My mother called on Tuesday. “Well?”

“I suppose.” I hated it when she was right. “You know how my toilet always kind of dribbled? Fixed.”

“Accessorize,” she said.

That night I shopped online. At first, all I wanted was to reward it for all the work it had done around the house. I bought an eight ounce bottle of Royal Carnauba, The King of Waxes. According to Amazon its polymer formula “created chains that cross-linked, allowing the polish to fill and level the micro-valleys in your machine’s paint.” I’d brushed up against it occasionally while we did the dishes and I’d been impressed by how sleek its finish was. At the bottom of Royal Carnauba’s Amazon page, in the Customers Who Bought This Item Also Bought section, were all kinds of aftermarket add-ons. I couldn’t resist adding a refurbished Audiostar voice card to my cart. It was on sale for half price and featured eleven accents including British Nigel, Irish Liam, Jamaican Desmon and Australian Heath. Then I discovered that customers who wanted to hear what their machines had on their minds also bought accessories of a more intimate nature.

I don’t know why this surprised me, but it did. Maybe it was because I had never wandered into the libidinous precincts of Amazon, or even suspected that they existed. I spent a pleasant half hour unable to stop reading the Most Helpful Customer Reviews or to ignore the fizzing at the base of my skull. The machine parked itself behind me, its headlights demurely dimmed. I was also surprised at how easy it was to imagine attaching these sex toys to the machine and making proper use of them. And why not? I was thirty-six years old. I could vote and I had a 401(k) account and my very own office. With a door. I settled on Lucid Dream’s Rebellious Ryan, a “sensually designed, power packed 3-speed arouser with an unbelievable fluttering butterfly.” With my Amazon Prime account, two day delivery was guaranteed and my mother didn’t have to know.

Unless she already did.

I awoke the next morning to find the machine in my bedroom, sorting clothes from a laundry basket into my dresser drawers. Not only had it ironed my jeans and tee shirts, but it was folding my panties. I noticed several unmatched socks in the trash bin. They had been living in the bottom of my sock drawer in the hope that their mates would return from laundry exile someday. When I went into the bathroom to shower, I discovered that it had lined up my shampoos and conditioners in size order on the edge of the bathtub. I turned the shower on and, as I waited for the hot water, I leaned into the door until it clicked shut.

When I came home that night it had made rosemary-encrusted roast chicken for dinner. Sides were garlic-mashed potatoes and sautéed asparagus sprinkled with black sesame seeds.

“How was the gravy?” asked my mother.

“Creamy.” I knew the machine was listening to my side of the phone conversation. “Better than yours.”

“Uh-oh.”

I had a late meeting the next day and didn’t get home until well after dark. There was a crab-stuffed Portobello mushroom and a Caesar salad waiting for me, as well as the package from Amazon. By the time I finished dinner it was eight-thirty. As I sliced the box open, I told myself I was too tired to try to install both of the new accessories before bedtime. Which would be simplest?

That night the earth wobbled on its axis. Rebellious Ryan had me shivering with pleasure. Then shuddering. Then quaking. I think it must have been after three in the morning when the tremors finally began to subside. I flopped onto bed, sated and sore and blessedly alone. I slept like a dead woman.

Hours passed. Perhaps epochs. Eons.

“Jennifer?” I had never heard my name spoken quite so tenderly. The voice was mellow and rich and unfamiliar. “I let you sleep in, love, but soon you’re going to be late for work.” Sonorous, plummy, British. I bolted upright and the machine was standing by my bed. “I’ve drawn water for your bath. What kind of cheese would you like in your omlette? We have cheddar, provolone and Swiss. ”

“You’re talking.”

“You’re surprised. Brilliant! I had some trouble detecting the voice card, but once I updated the drivers, everything was fine.”

I pulled the sheet up to my neck, throat tight, cheeks burning. Had I really clamped my legs around that sleek blue titanium chassis and yodeled? “I think I’d like some privacy.”

“Of course.” The machine rolled toward the door, then paused. “You know,” it said, “I wonder if we don’t want to change the color scheme in this room. Beige is so … beige, don’t you think? I was thinking of something in a raspberry.”

I waited until it had rolled down the hall before I called my mother.

“Can you email me the receipt?”

“Really? Returning it so soon?”

“Yes. It wants to redecorate.”

“At least it got your mind off that man.”

I hated it when she was wrong.